Food and Drinks

The national dish for most Ethiopians is injera, a flat, sour dough pancake made from a special grain called teff, which is served with either meat or vegetable sauces. Ethiopians eat these injera by tearing off a bit of injera and uses it to pick up pieces of meat or mop up the sauce. Berbere, the blend of spices which gives Ethiopian food its characteristic taste can be hot for the uninitiated, although vindaloo or hot curry fans will not have any problem.

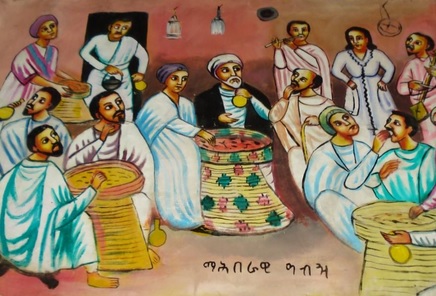

When eating national food Ethiopians eat together, off one large circular plate. Visitors and guests will have choice morsels and pieces of meat placed in front of them, and when eating doro wot, chicken stew, the pieces of meat are eaten last, after filling up on injera and sauce. You eat with your right hand, and should always wash your hands before eating.

Vegetarians should try “fasting food”, what Orthodox Christians eat during Lent and other fasting periods, and which is free of meat and animal products.

Ethiopia produces its own wines – Dukam and Goudar are two good, dry reds. Crystal is a dry white wine and Axumite is a sweet red – and spirits, like gin, ouzo and brandy. There are also traditional alcoholic beverages such as tela (a local beer made from grain), tej (honey wine or mead) and kati kala (distilled liquor).

Restaurant prices can vary from 3 birr in the cheaper restaurants to around 25 to 30 birr per head in a restaurant with national music and dancing. Prices do not generally include drinks.

Coffee

The story of coffee has its beginnings in Ethiopia, the original home of the coffee plant, coffee arabica, which still grows wild in the forest of the highlands. While nobody is sure exactly how coffee as a beverage came about, it is believed that its cultivation and use began as early as the 9th century.

Coffee Arabica, first discovered in the ‘Kaffa’ region (from which the name coffee is derived) in south western Ethiopia, grows wild in many regions of the country and has been used by Ethiopians for many years as a food, a beverage and a medicine. It now accounts for 65% of all export earnings.

Produced using three very distinctive methods – (the forest system, the small farm or cottage system and the plantation system) – Ethiopian coffee has earned itself a reputation as one of the finest, most flavourful coffees in the world. The forest system means coffee grows under a forest canopy and needs very little human interference. The small farm or cottage system is the most popular method for producing coffee in Ethiopia – in fact this method is responsible for 95% of all coffee production. The cottage system consists of small backyard gardens with a few coffee trees, which are harvested by hand. There are presently some 700,000 coffee smallholders who produce coffee in this way. The final method of production is the plantation system, which is becoming increasingly popular. This is farming on a larger scale using modern processing equipment and ensures more quality assurance advantages.

Dilla, the capital of Gedoa in southern Ethiopia is the home of some of the finest coffee plantations. Seven years ago there were only 33 industrial units for processing coffee in Dilla, now there are 200.

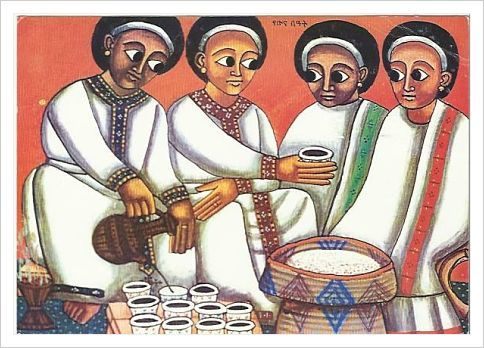

Ethiopia is the home of coffee. An intricate traditional coffee ceremony is performed in many households. This may also be seen in most of the larger hotels in Addis Ababa. The time devoted to the ceremony indicates how important the drink is to Ethiopians.

At the start of the ceremony a table is scattered with freshly-cut grass to give the fresh and fragrant scent of outdoors. A female attendant or the lady of the household sits on a low stool beside a charcoal brazier. She first lights a stick of incense to provide the right atmosphere. Guests are given a snack such as popcorn whilst the ceremony is proceeding. The green coffee beans are roasted in a pan and then ground with a pestle and mortar. Then the pot for boiling the coffee is produced, a round clay pot with a plump base and a long narrow neck and spout. After the water has been heated the coffee is added and brought to the boil. The coffee is poured into small, traditional cups and sugar is added. The coffee has a full-bodied flavour but it is not itself bitter.

Festival and Holidays Timkat – The Feast of Epiphany

This is the greatest festival of the year, falling on 19 January, just two weeks after the Ethiopian Christmas. It is actually a three-day affair, beginning on the Eve of Timkat with dramatic and colourful processions. The following morning the great day itself, Christ’s baptism in the Jordan River by John the Baptist is commemorated. The third day is devoted to the Feast of St. Michael, the archangel, one of Ethiopia’s most popular saints.

Since October and the end of the rains, the country has been drying up steadily.

The sun blazes down from a clear blue sky and the Festival of Timkat always takes place in glorious weather.

Enormous effort is put into the occasion. Tej and tella (Ethiopian mead and beer) are brewed, special bread is baked, and the fat-tailed African sheep are fattened for slaughter. Gifts are prepared for the children and new clothes purchased or old mended and laundered.

Everyone men, women, and children appears resplendent for the three-day celebration. Dressed in the dazzling white of the traditional dress, the locals provide a dramatic contrast to the jewel colours of the ceremonial velvets and satins of the priests’ robes and sequinned velvet umbrellas.

On the eve of the 18 January, Ketera, the priests remove the tabots from each church and bless the water of the pool or river where the next days celebration will take place. It is the tabot (symbolising the Ark of the Covenant containing the Ten Commandments) rather than the church building which is consecrated, and it is accorded extreme reverence. Not to be desecrated by the gaze of the layman, the engraved wooden or stone slab is carried under layers of rich cloth.

In Addis Ababa, many churches bring their tabots to Jan Meda (the horse racing course of imperial day) accompanied by priests bearing prayer sticks and sistra, the ringing of bells and blowing of trumpets, and swinging bronze censors from which wisps of incense smoke escape into the evening air. The tabots rest in their special tent in the meadow, each hoisting a proud banner depicting the church’s saint in front. The priests pray throughout the long cold night and mass is performed around 2:00 a.m. where huge crowds of people camp out, eating and drinking by the light of flickering fires and torches.

Towards dawn the patriarch dips a golden cross and extinguishes a burning consecrated candle in the altar. Then he sprinkles water on the assembled congregation in commemoration of Christ’s baptism. Many of the more fervent leap fully dressed into the water to renew their vows.

Following the baptism the tabots start back to their respective churches, while feasting, singing and dancing continue at Jan Meda. The procession winds through town again as the horsemen cavort alongside, their mounts handsomely decorated with red tassels, embroidered saddlecloths, and silver bridles. The elders march solemnly, accompanied by singing leaping priests and young men, while the beating of staffs and prayer sticks recalls the ancient rites of the Old Testament.

Id-Al-Adha -Festival of Sacrifice

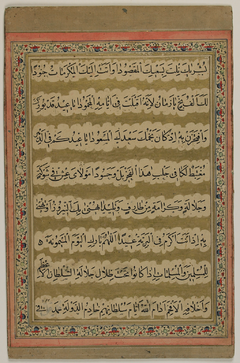

Eid al-Adha or “Festival of Sacrifice” or “Greater Eid” is an important religious holiday celebrated by Muslims all over the world to commemorate the willingness of Abraham (Ibrahim) to sacrifice his son Ishmael (Isma’il) as an act of obedience to God, before God intervened to provide him with a ram to sacrifice instead. The meat is divided into three parts: the family retains one third of the share, another third is stored and the other third is given to the poor and needy. Eid al-Adha is the latter of two Eid festivals celebrated by Muslims, the first being Eid ul-Fitr. Like Eid ul FitrEid, al-Adha begins with a prayer followed by a sermon. Eid al-Adha is celebrated annually on the 10th day of the 12th and the last Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah of the lunar Islamic calendar. Eid al-Adha celebrations start after the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia by Muslims worldwide. The date is approximately 70 days (2 Months and 10 days) after the end of the month of Ramadan. Ritual observance of the holiday lasts until sunset of the 13th day of Dhu al-Hijjah

Victory of Adwa

In 1896, Ethiopia fought a desperate battle against a stronger European nation attempting to invade, conquer, and colonize the smaller nation and more importantly, be able to exploit its natural resources. After a long siege in the mountains between Ethiopia and the bordering nation of Eritrea, a series of brutal battles were fought between the army of King Menelik II of Ethiopia and the Italian Army under the command of the Italian governor of Eritrea, General Oreste Baratieri. The mistrust between the two nations had begun 7 years before during the signing of the Treaty of Wichale (or Uccialli) agreed to in principle in May of 1889. Menelik II agreed to provide to Italy land in the Tigray province in exchange for support in the form of weapons the Italians had been supplying him for some time. The Italians wanted more. There were two versions of the treaty to be signed, one in Italian, and one written in Amharic. Unbeknownst to the conquering King was the fact that the version in Italian had been altered by the translators to give Rome more power over Menelik II and his kingdom of Ethiopia. The Italians believed they had tricked Menelik II into giving his allegiance to Rome in the treaty. Mistakenly, they believed him to be unsophisticated in the way the Europeans believed themselves to be. To the Italians surprise, the treaty was rejected despite their attempt to influence the king with 2 million round of ammunition. He would have none of it and denounced them as liars who had attempted to cheat himself and Ethiopia. When bribery failed Italy did what so many nations have tried throughout history. They attempted to set up Ras Mangasha of Tigray as rival by promising to support him with money and weapons, and hoped he would overthrow Menelik II who had denounced Italy. When that failed, the Italians turned to Baratieri, who had shown some promise in his handling of government affairs in Eritrea. Baratieri was no stranger to battle and devised a good strategy to lure the Ethiopians into an ambush. There were three main problems with his strategy. First, he had drastically underestimated the strength and will of the army facing him. Although aware he was outnumbered, the Governor of Eritrea believed the Ethiopians to be undisciplined and unskilled at the art of war negating the advantage in numbers. Certain he would have an advantage over the ‘savages’, he dug in his 20,000 troops and 56 guns at Adawa awaiting the King and his men.

In the meantime, Menelik II had trapped a thousand or so of the Italian army and besieged them. He agreed to allow them safe passage if Italy would reopen negotiations with him concerning a peace treaty. The Italian government refused and in fact did the opposite, authorizing more dollars to pursue the war in Ethiopia. Their Nations’ pride had been hurt by the African King and they sought to restore their ego and influence. The second error Baratieri made was the assumption he could lure the Ethiopians out into an ambush. He did not think they had the tactics or knowledge of battle he possessed as an important leader in a civilized European nation. After a 3 month standoff his troops were out of basic supplies and he had to move forward or retreat. After a message came from higher up in the government calling him out as ineffective and unsure, he was pushed ahead to attack. Baratieri’s third mistake of not understanding how poor his battle intelligence was became the most costly of his errors. The strategy he employed was to outflank the Ethiopian army under the cover of darkness and move in on them from the mountains above their camp. While Sun Tzu would have approved, the Italian commander did not account for the extremely harsh terrain nor would the lack of direction and difficulty in communicating with his men have out in the wild country. After setting out confident in their battle strategy, the officers in charge of implementing the attack learned how poor the rough sketches they had were. It was dark and cold in a high mountain pass in February and it was doomed. Divisions of Italian soldiers became confused, lost, and disorganized. Through the confusion a two mile gap in their battle line was opened and the Ethiopians rushed in cutting the Italian attack in two. Baratieri had failed to claim the high ground and Menelik II hastily moved his artillery in above the attacking soldiers. Able to lob shells down upon the invaders, the Ethiopians raced to seize the advantage but the Italians held their ground and at mid-morning it looked as if they may be able to win in spite of all the difficulty they had encountered. Considering retreat, Menelik II was persuaded by his advisors to commit to the battle an additional 25,000 soldiers he had been holding in reserve. Those additional troops proved to be the difference in the outcome of the ferocious melee. Having fought hundreds of battles to protect their homeland, Menelik’s warriors attacked with a ferocity the Italians couldn’t have imagined. Taking hardly any prisoners, the victors of Battle of Adwa killed 289 Italian officers, 2,918 European soldiers and about 2,000 askari. A further 954 European troops were missing, while 470 Italians and 958 askari were wounded. Some 700 Italians and 1,800 askari fell into the hands of the Ethiopian troops. With the victory at the Battle of Adwa in hand and the Italian colonial army destroyed, Eritrea was King Menelik’s for the taking but no order to occupy was given. It seems that Menelik II was wiser than the Europeans had given him credit for. Realizing they would bring all their force to bear on his country if he attacked, he instead sought to restore the peace that had been broken by the Italians and their treaty manipulation seven years before. In signing the treaty, Menelik II again proved his adeptness at politics as he promised each nation something for what they gave and made sure each would benefit his country and not a rival nation.

Fasika – Ethiopian Easter

On Easter eve people celebrate and go to church with candles which are lit during a colourful Easter Mass service which begins at about midnight Ethiopian time. People go home to break their fast with the meat of chicken or lamb, slaughtered the previous night, accompanied with injera and traditional drinks (i.e. tella or tej). Like Christmas, Easter is also a day of family re-union, an expression of good wishes with exchange of gifts (i.e. lamb, goat or loaf of bread).

Mawlid – Birth of the Prophet Mohammed

Millions of Ethiopian Muslims are celebrating the birth of their prophet, Muhammad, with a mass gathering prayer ceremonies and spiritual songs honoring the Prophet in various parts of Ethiopia.

Mawlid, a day of observance which occurs on the 12th day of Rabi’ al-awwal, the third month in Islamic calendar, falls between the evenings of 13 and 14 January. Prophet Muhammad was born in AD 570 and is thought by Muslims to be a messenger and prophet sent by God. His birthday is observed by prayers at mosque and charity for the poor.

Muhammad’s birthday is marked in different ways in different Muslim nations. Sufi Muslims in some countries such as Libya take out processions to mark the day. People wear traditional dresses to take part in these processions that often include singing and chanting of hymns and beating drums. Pakistan marks the day with a public holiday, gun salute and by hoisting national flag on all public buildings.

In Ethiopia, Muslims celebrate the holiday, in the morning at mosques with prayers and spiritual songs. Afternoons are dedicated to family gatherings and visits to family members or relatives.

Enkutatash – Ethiopian New Year

The Ethiopian New Year falls in September at the end of the big rains. The sun comes out to shine all day long creating an atmosphere of dazzling clarity and fresh clean air. The highlands turn to gold as the Meskel daisies burst out in all their splendour. Ethiopian children clad in brand new clothes dance through the villages giving bouquets of flowers and painted pictures to each household.

September 11th is both New Year’s Day and the Feast of St. John the Baptist. The day is called Enkutatash meaning the “gift of jewels.” When the famous Queen of Sheba returned from her expensive jaunt to visit King Solomon in Jerusalem, her chiefs welcomed her back by replenishing her treasury with enku or jewels. The spring festival has been celebrated since these early times and as the rains come to their abrupt end, dancing and singing can be heard at every village in the green countryside. After dark on New Year’s Eve people light fires outside their houses.

The main religious celebration takes place at the 14th-century Kostete Yohannes church in the city of Gaynt within the Gondar Region. Three days of prayers, psalms, and hymns, sermons, and massive colourful processions mark the advent of the New Year. Closer to Addis Ababa, the Raguel Church, on top of the Entoto Mountain north of the city, has the largest and most spectacular religious celebration. But Enkutatash is not exclusively a religious holiday, and the little girls singing and dancing in pretty new dresses among the flowers in the fields convey the message of springtime and renewed life. Today’s Enkutatash is also the season for exchanging formal New Year greetings and cards among the urban sophisticated in lieu of the traditional bouquet of flowers.

Meskel – The Finding of the True Cross

The festival of Meskel is second in importance only to Timkat and has been celebrated in the country for over 1,600 years. The word actually means “cross” and the feast commemorates the discovery of the Cross upon which Jesus was crucified by the Empress Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great. The original event took place on 19 March, AD 326, but the feast is now celebrated on 27 September.

Many of the rites observed throughout the festival are said to be directly connected to the legend of Empress Helena. On the eve of Maskel tall branches are tied together and yellow daisies, popularly called meskel flowers, are placed at the top. During the night these branches are gathered together in front of the compound gates and ignited. This symbolises the actions of the Empress whom, when no one would show her the Holy Sepulchre, lit incense and prayed for help. Where the smoke drifted she dug and found three crosses. To one of them, the True Cross, many miracles were attributed.

Meskel also signifies the physical presence of the True Cross at the remote mountain monastery of Gishen Mariam located in the Welo region. In this monastery is a massive volume called the Tefut, written during the reign of Zera Yacob (1434-1468), which records the story of how a fragment of the Cross was acquired.

In the Middle Ages, it relates, the Christian monarchs of Ethiopia were called upon to protect the Coptic minorities and wage punitive war against their persecutors. Their reward was usually gold, but instead the Emperor Dawit asked for a fragment of the True Cross from the Patriarch of Alexandria. He received it at Meskel.

During this time of year flowers bloom on the mountains and plains and the meadows are yellow with the brilliant Meskel daisy. Dancing, feasting, merrymaking, bonfires, and even gun salutes mark the occasion. The festival begins by planting a green tree on Meskel Eve in town squares and village marketplaces. Everyone brings a pole topped with meskel daisies to form the towering pyramid that will soon be a beacon of flame. Torches of eucalyptus twigs called chibo are used to light the bundle of branches called demera.

In Addis Ababa celebrations start in the early afternoon, when a huge procession bearing flaming torches approaches Meskel Square from various directions. The marchers include priests in their brightly hued vestments, students, brass bands, contingents of the armed forces, and bedecked floats carrying huge lit crosses. They circle the demera and fling their torches upon it, while singing a special Meskel song. Thousands gather at the square to join in and welcome the season of flowers and golden sunshine called Tseday. As evening darkens the flames glow brighter. It is not until dawn that the burning pyramid consumes itself and the big tree at the centre finally falls. During the celebrations each house is stocked with tella, the local beer, and strangers are made welcome.

Id Al Fater – The End of Ramedan

Eid-al-Fitr (Eid al-Fitr, Eid ul-Fitr, Id-Ul-Fitr, Eid) is the first day of the Islamic month of Shawwal. It marks the end of Ramadan, which is a month of fasting and prayer. Many Muslims attend communal prayers, listen to a khutba (sermon) and give zakat al-fitr (charity in the form of food) during Eid al-Fitr.