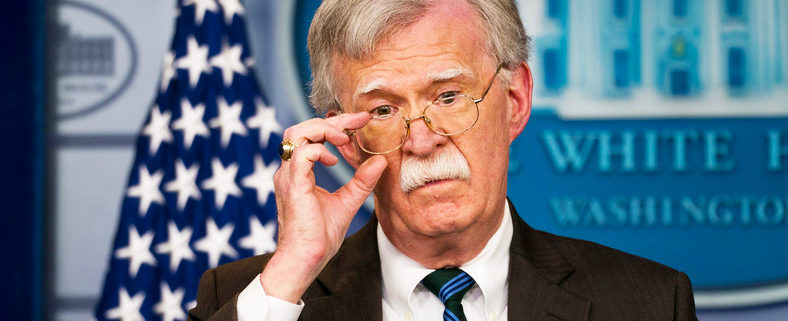

Bolton Outlines a Strategy for Africa That’s Really about Countering China (New York Times) (December 20, 2018)

WASHINGTON (December 13, 2018) — The Trump administration rolled out a new strategy for Africa on Thursday, but it was really all about China. John R. Bolton, President Trump’s national security adviser, said the United States

would lavish money and greater attention on the African continent, casting it as a crucial battleground in the global economic contest between the United States and China. But Mr. Bolton conceded that the United States had limited resources to compete with the tens of billions of dollars China is pouring into Africa. He also threatened to withdraw American aid for some United Nations peacekeeping missions, which he labeled ineffective, as well as for certain African countries like South Sudan that he said were corrupt or ungrateful. Mr. Bolton’s speech, at the Heritage Foundation, was his latest effort to flesh out what Mr. Trump’s “America First” foreign policy means for particular regions. In Africa, he said, the greatest threat came not from poverty or Islamist extremism but from an expansionist China, as well as Russia. “They are deliberately and aggressively targeting their investments in the region

to gain a competitive advantage over the United States,” Mr. Bolton said. “China uses bribes, opaque agreements and the strategic use of debt to hold states in Africa captive to Beijing’s wishes and demands.” Mr. Bolton announced a new program, “Prosper Africa,” to support American investment across Africa. Without attaching a dollar figure, he said the United States would facilitate alternatives to the large, state-directed public works

projects pushed by the Chinese. Those projects, he said, were turning some African countries into economic vassals

of China. Zambia, for example, owes Beijing $6 billion to $10 billion, according to Mr. Bolton, and is at risk of having the Chinese take over its national power company. China built a military base in another indebted African country, Djibouti, a few miles from where the United States has a base for counterterrorism operations.

Earlier this year, Mr. Bolton said the Chinese fired military-grade laser beams at American aircraft, injuring two pilots. Experts welcomed the focus on Africa, which has often been neglected by both Republican and Democratic administrations. But some noted the contradiction between Mr. Bolton’s promise of increased investment and a rollback of American engagement in other areas. “You can’t counter a multifaceted, long-term Chinese play just by increasing investment,” said Grant T. Harris, a former adviser on Africa to President Barack Obama. “Washington needs to understand that China is investing in relationships, not just infrastructure.” Mr. Trump famously asked why the United States should accept African immigrants, belittling their countries with an epithet. The first lady, Melania

Trump, made a four-country tour of the continent in October, which drew more attention for her wardrobe — particularly a colonial-style pith helmet on a safari in Kenya — than for her encounters with Africans.

Mr. Bolton traced his interest in Africa to his first job in government, working at the United States Agency for International Development during the Reagan administration. Yet he made clear that he viewed much of the American aid sent to Africa as wasted or misspent.

“From now on,” he said, “the United States will not tolerate this longstanding pattern of aid without effect.”

South Sudan, where rival leaders recently agreed to end a ruinous civil war, is among those at risk of losing aid. Mr. Bolton said the country was still being led by “the same morally bankrupt leaders” who prolong “horrific violence and immense human suffering.”

In the 2017 fiscal year, foreign assistance to Africa from the State Department and the Agency for International Development amounted to $8.7 billion. From 2014 to 2018, the United States provided some $3.8 billion in humanitarian aid to South Sudan and its neighbors. American businesses invested $50 billion in Africa in

2017, according to the State Department. The flow of money from China to Africa has been substantial, but much of it is not what experts consider aid. From 2000 to 2014, Chinese financing to Africa totaled $121.6 billion, according to an analysis by AidData, a research center based at the of William & Mary in Virginia. About 40 percent of that can be defined as aid, based on the parameters of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, according to Bradley Parks, AidData’s executive director. During the same period, the United States

provided $106.7 billion in aid, according to the group. Most of the Chinese money comes in the form of loans, many of which are for projects being built by Chinese state-owned companies. The contracts typically have strict conditions attached to them; borrowers often have to start repaying the loans within a few years, unlike loans from the World Bank, which can have a grace period of a decade. “The work that they do, the assistance that they provide, seems to be more about China than it is about the countries that are the target, or the recipients of the assistance,” said Mark Green, the administrator of the Agency for International Development.

But the Chinese companies have had great success in winning contracts for projects in Africa. In some cases, this is tied to bribing officials. But in others, Chinese companies have been good at managing relations because, unlike

American companies, they have a strong presence on the ground. “For American businesses to compete effectively in the region, the U.S. government must develop methods to come to the table with a full package,” said Mike Davis, an American businessman in Uganda. “The current approach has not proven effective when you compare it against the competition.” Mr. Trump, driven by a desire to confront China’s growing influence, signed a bill to double the war chest of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, which finances American businesses in developing nations. Starting in October, the agency will have $60 billion to dole out in the form of loans, loan insurance and

equity. But the agency’s chief executive, Ray W. Washburne, said projects that the agency finances still “have got to make economic sense,” adding, “The Chinese seem to be doing these loan-to-own programs.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!